Measuring Pain in the Clinic

Reliable and valid pain measurement is essential to gauging the effectiveness of the treatments we use. Measuring pain is more than just measuring its intensity. Pain interference (the self-reported consequences of pain activities and participation, including meaning and satisfaction in social relationships with family and friends and enjoyment of participation in work and social activities) is very important.

When assessing pain (and its interference), we need to remember that pain is always a subjective and personal experience. A person’s report of their pain experience should be respected, and we cannot conclude on the presence or absence of pain from activity in sensory neurons alone. For this reason, objective pain measurement tools are deemed inappropriate to use with patients. Instead, self-reported measures of pain, disability, and quality of life are recommended.

The recommended pain assessment will depend on a patient’s pain duration (acute vs chronic), pain condition and type (e.g. cancer, back pain, neuropathic pain), population type (e.g. children, individuals with cognitive impairment), and patient values, goals and preferences.

This article is not an exhaustive list of pain measures. It will provide an overview of commonly recommended measures (e.g. visual pain scale, pain chart faces) that clinicians can use to aid their assessment of a patient’s pain. If you have suggestions about additional tools, please contact secretary@efic.org.

- Acute pain

- Numerical rating scale (NRS)

- Visual analog scale (VAS)

- Faces Pain Scale Revised

- Chronic pain

- The Brief Pain Inventory – Short Form (BPI – sf )

- The Short form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ)

- The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)

- Type of pain condition

- Measuring cancer pain and pain in palliative care

- Assessment of pain in patients with communication problems and in dementia

- The COMFORT Pain Scale

- Face–Legs–Activity–Cry–Consolability (FLACC)

- The CRIES Pain Scale

- The MOBID-2 Pain Scale

- The EQ-5D-5L

- The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11)

- The PAIC

Acute pain

Acute pain can be assessed both at rest and during movement using one-dimensional tools. We discuss three:

Numerical rating scale (NRS)

As the name suggests, the NRS uses numbers to rate pain. The NRS can be used by individuals >8 years old to measure worst, least, or average pain over the last 24 hours, or during the last week. It uses a defined scale, and asks patients to verbally give a number to match their pain, place a mark on the number indicating their pain, or even point to the number. The scale goes from from 0-10 or 0-100. Zero indicates the absence of pain, while 10 or 100 represents the worst possible pain. The NRS is quick and easy to understand. One can use it to measure pain virtually, or over the telephone.

Visual analog scale (VAS)

The visual analog scale (also called visual pain scale) or VAS for short, instructs a patient to mark a point on a defined scale to indicate their pain intensity. Like the NRS, the VAS can be used to measure worst, least, or average pain over the last 24 hours, or during the last week. While the VAS can be quick to use, it is not as practical as the NRS as it requires clear vision, dexterity, paper, and pen.

Faces Pain Scale Revised

The Faces Pain Scale (sometimes called smiley face pain scale) uses six faces to measure pain in children – usually between 3 and 8 years old. As part of this face rating scale, the child is asked to point to the face that best represents their pain intensity all the way from the face on the left that shows no pain up to the one on the right that shows lots pf pain.

Chronic pain

Since chronic pain involves more complex physical, psychological, and social impairments than acute pain, multidimensional measurements – that measure more than just current pain intensity – are recommended. We will describe a few.

The Brief Pain Inventory – Short Form (BPI-SF)

The BPI measures pain intensity and the degree of interference with functioning, using a 0 – 10 numerical rating scale. It can be used to measure worst, least, or average pain over the last 24 hours. It measures pain interference in seven areas: 1) general activity, (2) walking, (3) normal work, (4) relations with other people, (5) mood, (6) sleep, and (7) enjoyment of life.

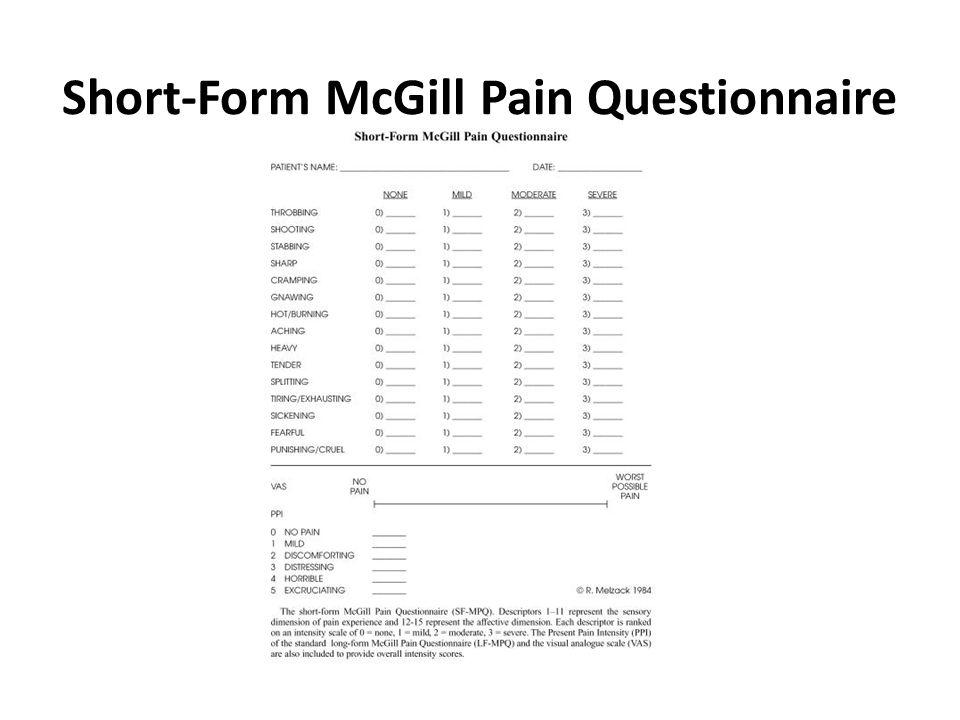

The Short form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ)

The SF-MPQ measures sensory, affective–emotional, evaluative, and temporal aspects of pain. It consists of 11 sensory (sharp, shooting, etc.) and four affective (sickening, fearful, etc.) verbal descriptors. The patient is asked to rate the intensity of each descriptor on a scale from 0 – 3. Three pain scores are calculated: the sensory, the affective, and the total pain index. Patients also rate their present pain intensity on a 0 – 5 scale and a visual rating scale.

The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)

The SF-36 measures health related quality of life using eight scales: physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health.

Each of the eight scales is directly transformed into a 0-100 scale on the assumption that each question carries equal weight. The lower the score the more disability. The higher the score the less disability i.e., a score of zero is equivalent to maximum disability and a score of 100 is equivalent to no disability.

Type of pain condition

There are a number of pain measurements created for the assessment of specific pain conditions. For example,

- The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) or Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) for low back pain

- The Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) for hip and knee osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS) for pain due to rheumatoid arthritis

- The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) to assess upper limb functional abilities

- CPRS Severity Score (CSS) for assessing complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- The Headache Impact Test for chronic headache disorders

- The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) measure fibromyalgia (FM) patient status, progress and outcomes.

These can be combined with more generic measurement, including the numerical rating scale (NRS) or visual rating scale (e.g VAS).

For neuropathic pain, there are a number of measures available. We discuss a few.

- The Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) is a 7-item pain scale, including the sensory descriptors and items for sensory examination. It is scored out of a total of 24. A patient with a score of 12 or more on this scale is diagnosed as suffering from neuropathic pain to some degree.

- The Neuropathic Pain Scale (NPS) contains 12 items: 10 related to sensations or sensory responses and 2 related to affect. For each item, the patient is instructed to rate their pain from “0” (no pain) to “100” (worst pain possible). Subjects with scores below 0 are predicted to have non-neuropathic pain, while those with scores at or above 0 are predicted to have neuropathic pain.

- PainDETECT (PD-Q) is a 9-item self-report screening questionnaire developed to detect neuropathic pain in conditions like chronic low back pain. PD-Q measures 7 aspects of the quality of the pain experienced, the chronological pattern (time course), and whether or not the pain radiates. It is scored from 0 to 38, with total scores of less than 12 considered to represent nociceptive pain, 13–18 possible neuropathic pain, and >19 representing >90% likelihood of neuropathic pain.

Measuring cancer pain and pain in palliative care

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [discussed earlier] is commonly used for cancer pain measurement.

In palliative care, pain is measured in scales that also measure other symptoms. For example, The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System measures 9 items: pain, activity, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, well-being, and shortness of breath.

Other measurements including a pain assessment include the Memorial Pain Assessment Card; Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) and a Short Form (MSAS-SF); M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI); the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist; and the Symptom Distress Scale.

Assessment of pain in patients with communication problems and in dementia

When a patient is unable to communicate their subjective pain experience, proxy measures must be used. These include observations of pain behaviours and reactions that may indicate that the patient has pain. We discuss a few below.

The COMFORT Pain Scale

This scale measures distress in unconscious and ventilated infants, children, and adolescents using nine items: alertness; calmness or agitation; respiratory distress; crying; physical movement; muscle tone; facial tension; arterial pressure; and heart rate. Each item is scored between 1 and 5.

Face–Legs–Activity–Cry–Consolability (FLACC)

This scale measures 5 categories of pain behaviours: facial expression; leg movement; activity; cry; and consolability. It has been validated for scoring postoperative pain in infants and children 2 months to 7 years old.

The CRIES Pain Scale

It uses 5 categories to assess distress: crying; requires O2 for saturation below 95%; increased vital signs (arterial pressure and heart rate); expression—facial; and sleepless. Each item is scored from 0-2. This scale is validated for neonates, from 32 weeks of gestational age to 6 months.

The MOBID-2 Pain Scale

This scale is used to measure pain of people living in nursing homes and patients with dementia. It is based on patients’ behaviour in connection with standardized active, guided movements of different body parts and pain behaviour related to internal organs, head, and skin.

The EQ-5D-5L

The 5-level EQ-5D assess five dimensions of a patient’s self-rated health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. Each patient is asked to tick the box next to the most appropriate statement in each dimension to indicate their current health state. This represents a 1-digit number which expresses the level selected for that dimension and is combined with other scores to create a 5-digit number which represents the patient’s health state.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) International Classification of Diseases 11TH Revision (ICD-11)

ICD is an international standard diagnostic tool for epidemiology, health management, research and clinical purposes, as well as the international standard for reporting of diseases and health problems developed by the WHO. ICD can be used to record individual health conditions, and to generate and share data on these conditions for a variety of purposes, including research, reimbursement and policy planning.

The inclusion of pain as a disease in ICD-11 is a key development which came into effect in 2022. It will facilitate the recording and reporting of pain symptoms diagnoses in a standardised format.

ICD-11 recognises the biopsychosocial nature of pain by defining chronic pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage. Chronic pain is pain that persists or recurs for longer than 3 months. Chronic pain is multifactorial: biological, psychological and social factors contribute to the pain syndrome.”

Additionally, Chronic Pain (MG30) has the following subsections with their own classification codes, which in turn will likely support pain management and treatment:

– MG30.0 – Chronic primary pain

– MG30.1 – Chronic cancer-related pain (new to ICD-11)

– MG30.2 – Chronic postsurgical and post traumatic pain (new to ICD-11)

– MG30.3 – Chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain

– MG30.4 – Chronic secondary visceral pain

– MG30.5 – Chronic neuropathic pain (new to ICD-11)

– MG30.6 – Chronic secondary headache or orofacial pain

For more information on pain measurement please visit www.immpact.org

The PAIC15

The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC 15) scale is an assessment scale for people with cognitive impairments, such as dementia, whereby facial expression, body movements and vocalizations are assessed. The PAIC 15 scale contains a total of 15 behavioural descriptors, with 5 behavioural descriptors for each behavioural category of facial expressions, body movements and vocalizations. The facial expression category includes items such as “frowning” and “narrowing the eyes”. Examples for pain-indicative body movements are “restlessness” and “guarding”. “Groaning” and “shouting” are examples from the vocalization category. For each of these behavioural descriptors a brief explanation is given to better illustrate the exact meaning of each descriptor.

Resource available at: https://paic15.com/en/start-en/

References:

Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, Keefe F, Mogil JS, Ringkamp M, Sluka KA, Song XJ. The revised IASP definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976.

Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Breivik Hals EK, Kvarstein G, Stubhaug A. Assessment of pain. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2008;101(1):17-24.

Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(7):798-804.

Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale–Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173-83.

Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. The Journal of Pain. 2004;5(2):133-7.

Melzack R. The short-form McGill pain questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30(2):191-7.

Bennett R. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ): a review of its development, current version, operating characteristics and uses. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2005;23(5):S154

Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, Kosinski M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6™) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):357-67

Harden RN, Maihofner C, Abousaad E, Vatine JJ, Kirsling A, Perez RS, Kuroda M, Brunner F, Stanton-Hicks M, Marinus J, Van Hilten JJ. A prospective, multisite, international validation of the Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Severity Score. Pain. 2017;158(8):1430-6

Bennett M. The LANSS Pain Scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001;92(1-2):147-57.

Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology. 1997;48(2):332-8.

Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. Pain DETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2006;22(10):1911-20.

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. Journal of Palliative Care. 1991;7(2):6-9.

van Dijk M, de Boer JB, Koot HM, Tibboel D, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden HJ. The reliability and validity of the COMFORT scale as a postoperative pain instrument in 0 to 3-year-old infants. Pain. 2000;84(2-3):367-77.

Crellin DJ, Harrison D, Santamaria N, Babl FE. Systematic review of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability scale for assessing pain in infants and children: is it reliable, valid, and feasible for use?. Pain. 2015;156(11):2132-51.

Krechel SW, Bildner J. CRIES: a new neonatal postoperative pain measurement score. Initial testing of validity and reliability. Pediatric Anesthesia. 1995;5(1):53-61.

Husebo BS, Ostelo RW, Strand LI. The MOBID‐2 pain scale: Reliability and responsiveness to pain in patients with dementia. European Journal of Pain. 2014;18(10):1419-30.

Kunz M, de Waal MW, Achterberg WP, Gimenez‐Llort L, Lobbezoo F, Sampson EL, van Dalen‐Kok AH, Defrin R, Invitto S, Konstantinovic L, Oosterman J. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): A multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta‐tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. European Journal of Pain. 2020 Jan;24(1):192-208.